|

.

FACE FORWARD:fRINGE Interview with Artist GWEN HARDIE

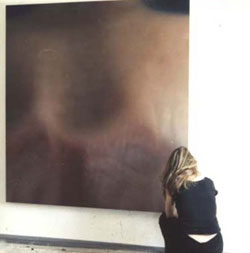

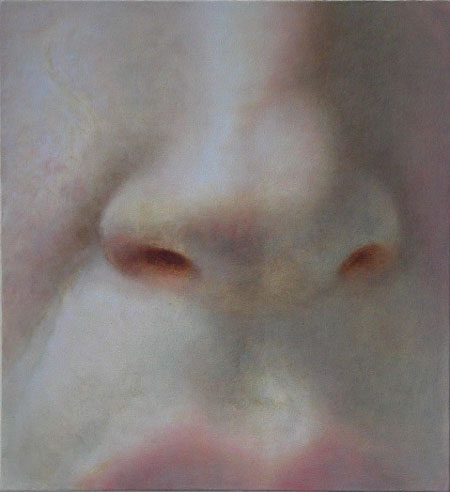

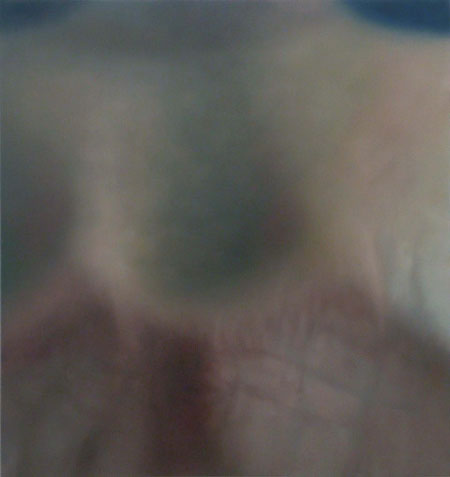

Graceful and unassuming, when you see artist Gwen Hardie standing next to her paintings, it seems that their subtle shifts in color and texture had emanated naturally from her. In her most recent work, Face Paintings, on view at Dinter Fine Art, Hardie embarks upon an introspective exploration of the formal and conceptual qualities of the human face. Certainly one of the most pervasive images in the history of art, painters have sought to depict the face as a means of memorial and homage or simple portraiture. Hardie’s seeks an entirely different purpose with her paintings however, using the human face as the device for intense formal visual analysis of the details of texture and light on the skin as well as creating extraordinarily intimate views of her sitters. Often monumental in scale, Hardie tightly crops many of the canvases so the viewer sees only the sensual curve of the nose, or the dramatic tension in the tenebrism of a cheek or jaw emerging from shadow. Although the face is the primary means of recognizing a person, we most often do not get close enough to explore these details—except possibly when making love. As such, the Face Paintings have a cool, raw intensity that present a rare balance in the painterly study of subject and the spiritual connection to the object of focus. Hardie came to New York in 2000 after years of working in Europe and the U.K. creating series of paintings that range from feminist treatments of the female form in her early career to non-objective paintings that fixate on the texture and colors of unseen “objects” emerging from the picture plane. Hardie’s contemplative painting seems to have evolved to this point free from the “sensationalized” London artists busy finding ways to float a dead shark in glass and the best way to affix dung to canvas, although she had six solo shows in London during the 90s. Certainly, fine work emerged from that school of artists, but to see the transition of Hardie’s oeuvre up to the Face Painting series, it becomes clear that she is something different. Dee Dee Vega: Many of the works in your Face Paintings seem to treat the surface of the face as an emotional landscape. What is it about the face or about your sitters that interests you? Gwen Hardie: When we look at a person’s face, we automatically notice the surface details of the skin and their features. We also absorb something of the inner state of that person—the idea of looking at the surface and through it at the same time is visually and psychologically interesting. DV: Where did your interest in exploring the body—and later the face as subject matter begin? GH: As a child, I used to draw my family and myself, it was a way to try to understand and make sense of life around me. I felt like I was touching the issue of inhabiting a body more deeply by observing it and trying to recreate it in two-dimensional form. This developed in a more studious fashion at Art School, when I studied models for five years at Edinburgh College of Art in Scotland. DV: I understand that you evolved from politicized, conceptually feminist depictions of women in your early career to non-objective works. Now you are making semi-abstracted (or more precisely, highly cropped to the point of abstraction)—images of the face. Can you describe the artistic transition between these shifts of subject and style? GH: My early work was often interpreted as an attempt to reinvent the female form from a woman’s perspective—which in a way is accurate—although in retrospect, it also came out of the attempt to depict both an objective and a subjective response to the subject. In other words, it was an attempt to juxtapose how things look from the outside with how things feel from the inside, to subvert the gaze of the voyeur, to close the gap between self and other. My most significantly non-objective work called Verge was done between 2000 and 2004. I was trying to find a way of describing the visual act of focusing, rather than the object of focus. It was a helpful project that allowed me to explore subtle shifts of tonality and color combinations that created the illusion of a depth of field, with varying degrees of focus on an imaginary central point of light and dark. After 4 years I was curious about applying what I had learned to an actual point of reference again, and these Face Paintings are the result. DV: The body has remained an important focus in your painting. Is your interest conceptual or rooted in formal qualities of the body as art object? GH: The body is interesting in so far as it represents human existence, so I guess the interest is more conceptual. The issue of impermanence and human frailty is witnessed so clearly on the human surface. I also like the immediacy and the intimacy of painting something that people can easily identify with. DV: During the 90s, London became the world commercial art capital and you were living there at the height of it. Did this external circumstance influence your painting or do you see yourself as evolving independent of the rise of prominence of British artists and the London art scene? GH: I felt that the soulful, introspective nature of my work was not entirely in sink with most of the art that rose to dominance in London at that time, although I was very interested in Rachel Whiteread’s explorations of inner/outer space. I was fortunate enough to have 6 solo shows in London during that time. DV: The works in Face Paintings range from being relatively small to nearly monumental canvases. What dictates the size of the canvas? GH: The smaller the painting the more information is given, the larger the painting, the tighter the crop. Scale affects the way we experience things—the larger works take on a more all encompassing physical presence, one person recently told me she felt vibration running through her body while looking at the largest painting in the show which I think in part is to do with the subtle tonal and color shifts that prevent the eye from resting anywhere on the surface of the painting. The small works in the show are done during my residency at Yaddo last summer where I was more concerned with describing light effects on the skin with as much accuracy and economy as possible. DV: Do you see any shift in focus from form (or technique) to subject in the larger or smaller canvases? GH: Definitely. The larger paintings are so hugely magnified that they are almost unrecognizable, so one experiences a “back and forth” of the form coming into focus and dissolving. In the smaller ones, more information is given so they are less ambiguous. DV: Your earlier non-objective paintings share in common with Face Paintings an extremely sensual surface quality. Is there a conscious connection in the artistic process between the two bodies of work? GH: The surface quality is what carries the viewer into the work on a visceral level so I am very conscious of the importance of the surface. In both groups of work, the paint is applied wet into wet quickly so that the surface comes together seamlessly. DV: You’ve studied with many prominent artists and have been involved in several art communities. What influences have you drawn from these specific sources? GH: Berlin, London, New York…lets see, I discovered Baselitz work when I was in Berlin (1984-1990) on a DAAD Scholarship and was able to study with him for 6 months. I wanted to take on and work through new influences, as my art school training previously had been all about studying from life. I was attracted to Baselitz’s treatment of the single figure, the painterly devices he used to come up with unpredictable results, which served to unlock a kind of visceral and subjective reality from his subject. I experimented with gestural brushmarks and high contrasting colors—to the horror of my London dealer at the time—but ultimately found that the heightened moods and raw expressionist paint surfaces were just not what I was looking for. I eventually wiggled out of an expressionist framework by seeking influence from the distilled contours of Oskar Schlemmer. If my six years in Berlin were characterized by working through influences, the following 9 years in London were marked by a need to delve deeper into my own ‘archaeology.’ My work became more contemplative and connected to what was going on in my life. The desire to come to New York took root when I was seventeen. I remember visiting the Tate Gallery’s American Abstract Expressionist and Minimalist collections and feeling this surge of wild potential and enthusiasm. The spirit of visual and cerebral play in abstraction was a contrast to the British Figurative Tradition I had grown up with. After moving here in 2000, I painted the series Verge (2001-2004) which is a kind of tribute to painting of that generation, and more specifically the painterly surfaces of Rothko and the conceptual ideas of James Turrell, as well as being a more personal exploration of painting. More recently, I have been inspired by how Alex Katz and Chuck Close in very different ways address both abstraction and figuration in their treatment of faces. Oddly enough, I also feel very connected to the small and intimate paintings of a British woman painter called Gwen John, who my father named me after! www.dinterfineart.com. |

|

By Dee Dee Vega

By Dee Dee Vega

Gwen Hardie’s Face Paintings are on view at Dinter Fine Art through 23 December located at 547 West 27th Street. Please contact Ingrid Dinter for inquires about the artist at 212.947.2818 or at—

Gwen Hardie’s Face Paintings are on view at Dinter Fine Art through 23 December located at 547 West 27th Street. Please contact Ingrid Dinter for inquires about the artist at 212.947.2818 or at—